Ask Questions – Step 7 in “Encouraging Kids to More Cooperative Behavior”

Getting Kids to Listen Can be as Simple as Asking a Question!

My last post was with regards to the need to develop children’s inner locus of control and the fact that children who develop a strong inner locus of control are also more successful academically and in other areas of life.

One of the benefits of passing the locus of control to the child is that we often win more cooperation from them.

In addition to choices, asking children questions is another tool which can turn the locus of control over to the child while providing the structure and outcome required.

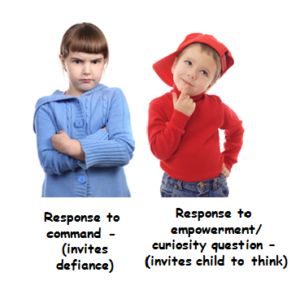

So often we give children command after command. “Get your jacket on!” “Brush your teeth!” “Put your dishes in the dishwasher!” Image how many commands a child hears in a day! Usually this creates a lot of resistance in children and they are apt to tune out. (Wouldn’t you?)

But when we rephrase the request in the form of a particular type of question, we invite a totally different response.

In Positive Discipline they are called “curiosity questions” and I like to call them “empowerment questions” as well because they empower kids to think.

For example, as alternates to two of the commands above – i.e. if instead of “Get your jacket on!” – we ask “What do you need to do so you’ll be warm outside?” or instead of “Brush your teeth!” we ask “What do you need to do so that your teeth are bright and shiny?” – the child is much more liable to respond in a cooperative manner.

As in the case of when we follow a choice with “you decide” (see last blog post), by asking this type of question, we invite the child to think and by doing so turn the locus of control over to them.

When we give a command, we hold the power. When we ask a curiosity question or empowerment question we turn the power over to the child. Note the expected outcome is the same, but the means by how it is reached is much more respectful.

The two different looks that often come to a child’s face when they are given a command vs. a choice applies with curiosity questions too. Watch for it!

Next Post:

The brain science behind “how we say something is more important than what we say”.